Is it possible to paint a landscape with innocence in 2015?

This year I have been up before dawn painting in the desert of La Guajira or on the shores of the Caribbean in Colombia and high up in the Sierra Nevada di Santa Marta, also in Colombia and at various times of the day, through the changing landscapes until nightfall.

I have painted on the Greek island of Aegina and in the hills above Florence getting up before the sun rises to start painting before the rest of the world wakes up. To live the illusion that I have the world to myself.

I have travelled and painted on Greek islands for over 40 years, since the 1970s. I cannot ignore the fact that some of the places where I have spent time painting are now the subject of different images: dead children, desperate strangers, a confusion of new “visitors”. Molyvos on the island of Lesbos, Pythagorion on Samos, Rhodes – all “border islands”, now frequently in the news as refugees and migrants arrive, alive or dead, on their shores.

This year I painted other seas as I read Kazantzakis’ Modern Greek translation of Homer’s Odyssey. Greek waters were never innocent or free from danger. Odysseus’ travels represented both physical and psychological dangers. The sea can never be fully trusted and must be respected, like nature that we seek to tame.

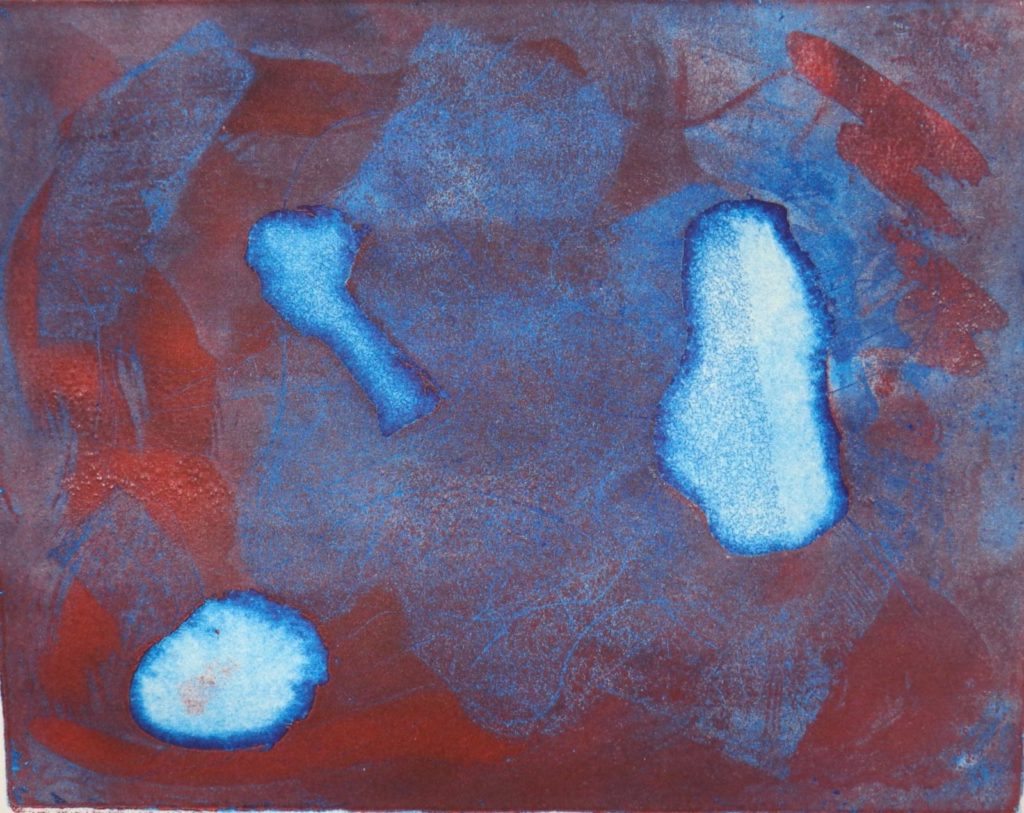

But I also believe in the power and mystery of paint and the act of painting. That through it we try to probe the mystery of our relationship with the other, our place in the world.

The images in this exhibition may have been painted in situ or completed in the studio or painted from various sketches with Keats’ words in mind, to portray “emotion reflected in tranquility”. But they are as much about paint as about a particular place.

So I return to the words that I have used to describe the body of work under the title: “Thalassa- A Greek Island Odyssey”: “Thalassa” is “Sea” in Greek. These paintings, from my journeys to some of the thousands of Greek islands, have merged with myths and poems that have coloured my perception and accompanied my travels – from Homer, to Sappho, Ovid, Byron, Cavafy and TS Eliot- their words mingling with my own. Above all, coming from England, the impact of the Greek light was like having veils removed from my eyes, to see the world for the first time in all its shining glory. I could believe that Apollo, the sun god, was born on Delos and Aphrodite from the sea’s foam near Paphos. Rocks become sea nymphs; mountains are sleeping gods; winds are blown by demi-gods and the sea’s quixotic nature, from silvery calm to dark turbulence, is the force against which, like Odysseus, we test ourselves.

John Berger’s words are an assertion of the continuing relevance of painting through the centuries and for us today: “Deep in the cave, which meant deep in the earth, there was everything: wind, water, fire, faraway places, the dead, thunder, pain, paths, animals, light, the unborn … They were there in the rock to be called to. The famous imprints of life-size hands (when we look at them we say they are ours) – these hands are there, stencilled in ochre, to touch and mark the everything-present and the ultimate frontier of the space this presence inhabits.

Painting throughout its history has served many different purposes, has been flat and has used perspective, has been framed and has been left borderless, has been explicit and has been mysterious. But one act of faith has remained a constant from palaeolithic times to cubism, from Tintoretto (who also loved comets) to Rothko. The act of faith consisted of believing that the visible contained hidden secrets, that to study the visible was to learn something more than could be seen in a glance. Thus paintings were there to reveal a presence behind an appearance – be it that of a Madonna, a tree or, simply, the light that soaks through a red”.

Rea Stavropoulos 2015-6