Success can impose limitations on an artist’s work and on how they are perceived. Helen Allingham’s name will forever be associated with the cottage garden watercolours which were so popular during her long and active life as a painter. Through this work she was the first woman to be elected as a full member of the Royal Watercolour Society in 1890, continuing to exhibit with the Society regularly until her death in 1926. Her influence went far beyond her own life to give us a certain enduring image of an English garden: tranquil scenes of domesticated nature with colourful herbaceous borders acting as frames for pretty women and children. Even in her own lifetime they were comforting illusions of a “Happy England” – the title of one of her books of paintings – that was fast disappearing through increasing urbanisation and industrialisation.

So the lawyers, stockbrokers and judges who bought her paintings were embracing a myth of vanished Englishness that could possibly be equated with the Arthurian romances of her Pre Raphaelite contemporaries. I myself was inspired by memories of Allingham’s paintings to create a garden on a Tuscan hillside when I felt a certain nostalgia for England while living in Italy! But the facts of Allingham’s life challenge preconceptions. I co-curated the exhibition “Beyond Watercolour Gardens: Helen Allingham Revisited” at Burgh House & Hampstead Museum in 2016*, exhibiting my own work alongside Allingham’s to provide a fresh perspective to her life and work. I became increasingly interested in her, both as an artist and in the woman behind the work when I discovered that as a young woman she was also a successful illustrator admired by Van Gogh. I amended her Wikipedia entry to include this overlooked fact, corroborated in Van Gogh’s letters.

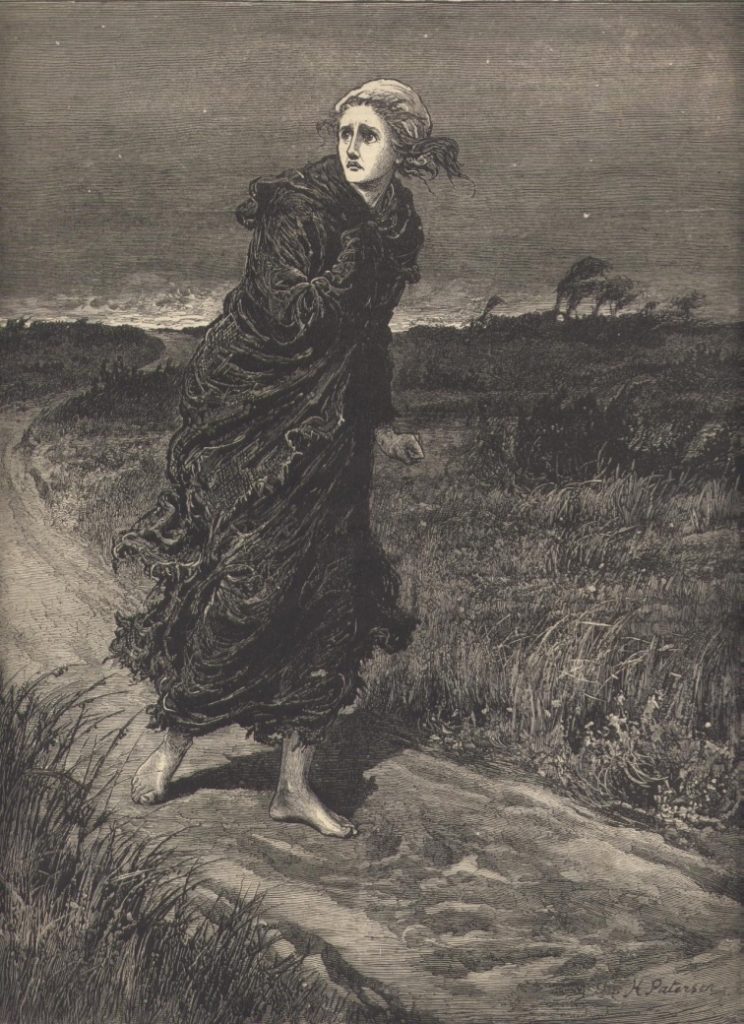

Helen Allingham (née Paterson) was born in 1848, the eldest of seven children. Her father died when she was fourteen. Her talent for art was encouraged, and she followed her aunt Laura as a student at the Royal Academy Schools, only the second woman to be accepted. She began to work as a professional illustrator in London almost immediately, going out and about to sketch flower shows, theatre performances, sporting events and scenes of street life for various illustrated journals, including “The Graphic”, for which she became a full time salaried employee, thus able to support her siblings, though still in her early twenties. To understand just how significant this publication was for the society and art of the time, it is enough to say that when he was teaching himself to draw by studying English illustrated magazines, Van Gogh bought volumes covering 10 years of “The Graphic”. On a recent visit to a library in Florence frequented by expatriates since the 19th century, I saw shelves full of “The Graphic” and could estimate that 10 years of bound volumes covered several feet. Helen Paterson illustrated Thomas Hardy’s “Far from the Madding Crowd”, his first novel to be serialised in the “Cornhill” magazine and he described her as his best illustrator.

When Helen Paterson married William Allingham, poet and editor of “Fraser’s Magazine”, a man nearly twice her age, she became Helen Allingham. The illustration work ceased and her watercolour career began. There is evidence that she was still highly regarded as an an artist and illustrator: George Eliot wrote to William asking if “Mrs A” would consider illustrating her novel “Romola” in its next edition as she did not much care for Leighton’s illustrations. Lord Leighton was the celebrated painter and President of the Royal Academy. We do not know why Eliot did not contact Allingham directly. She never did illustrate “Romola”. In marrying an older man who was a founding member of the Pre Raphaelites, highly respected by the artistic and literary world of the time, she frequented a circle of people older than herself: Tennyson, Carlyle, Julia Margaret Cameron, and she was now a married women who proceeded to have three children. Her watercolour career fitted more easily with the duties of running a household, caring for husband and children. But it is obvious that she retained her own ambitions for her work in continuing to paint and exhibit throughout her life. As well as joining the RWS, she was represented by the Fine Art Society in Bond Street and continued to exhibit there.

She moved home several times, moving to Hampstead in 1888 for the children’s education and her husband’s health and lived there in Eldon House until her death. William died in 1889 and Helen never married again. Perhaps she had greater personal freedom after that. She was still well liked by his friends and a frequent visitor to the Tennysons’ various homes. She was commissioned by Tennyson to produce a series of paintings of these homes and their gardens for another popular book.

Together with her friend Kate Greenaway, they would take the train from London and set out on sketching expeditions in the Surrey countryside, and I like to think of these two women sharing their mutual pleasure in painting outdoors, enjoying the sense of freedom that it gave them. In continuing to work as a painter throughout her life, able to paint and sell what she enjoyed, while remaining closely involved with children and grandchildren, Allingham displayed the insistence, persistence, resilience and strength required for an artist and remains an inspiration for women in the twenty-first century.

* See You Tube video “Rea Stavropoulos introduces “Beyond Watercolour Gardens: Helen Allingham Revisited”” for a 15 minute gallery talk and tour of the exhibition

copyright Rea Stavropoulos 14 October 2018